AInvention: Can an Artificial Intelligence Be An Inventor?

If you ask the movies, the answer is a resounding “Yes!” SciFi offerings have long posited a startling, often menacing future, in which technology itself surpasses people’s ability to do everything, including inventing technology itself.

When the Cyberdyne systems AI becomes “self-aware,” it immediately fashioned the “living tissue over metal endoskeleton” Terminator (Model 101), then followed up with a shockingly advanced new version in Terminator 2, Judgment Day (Series 1000), a molten metal nightmare that could morph into any person’s shape that it touched, flow around anything, turn itself into sharp weapons, and disappear into the floors. And, like their AI creator, they were inventive, as Hollywood would have it, mainly in the way they lay waste to humanity.

“Me?! The First Invention by AI? I never thought of it that way! I’m the Terminator. Aren’t I the End of Everything?”

But is it truly likely, or even possible, for machines to be inventive, in real life?

Many experts note that intelligence is just a naturally-arising technology, residing in our brains. And any technology can be reverse-engineered. From this logic, human-level artificial intelligence, with the ability to invent, just like us, appears to be guaranteed, and just a matter of time.

Others argue that invention by AI is plainly already taking place, right before our eyes. For example, we task complex AI neural networks with creating complex designs, including AI computer chips themselves.

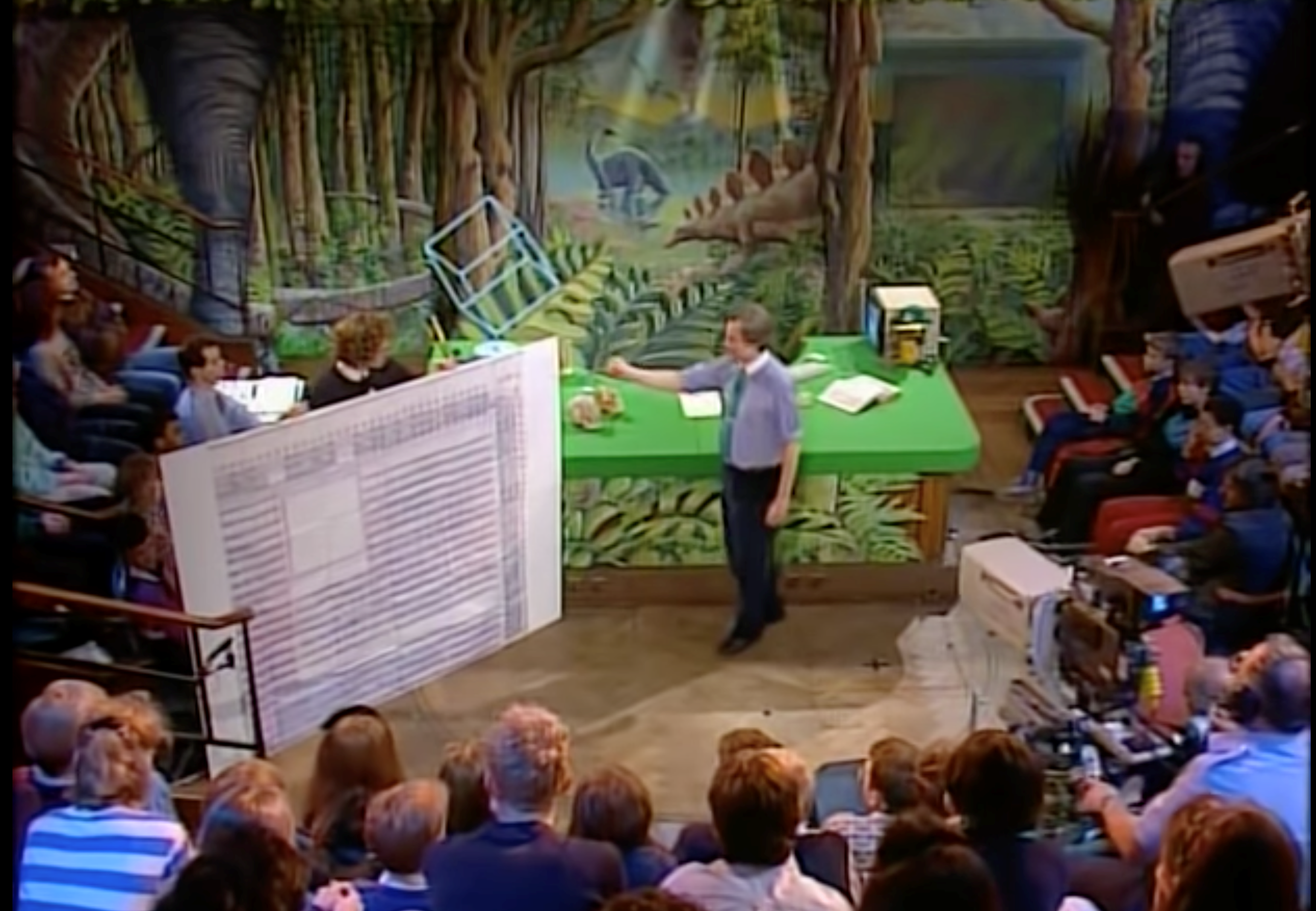

As Sir Richard Dawkins pointed out at the Royal Institution over 30 years ago, it is advanced computers that design our enormously complex computer chips.

“Let your eye roam over this remarkable document, and realize that no human could really sit down and design that.”

Given an infinite lifetime, a person could, perhaps, draw the dizzying enigma that is a chip schematic, except that any human would die, or kill themselves, before reaching that infinity.

AInvention

OK, so the possibility of machines becoming inventive is not only likely, it’s already here. Machines are inventing things, daily. That ends the discussion, right? We should expect all manner of AI inventors to begin cropping up in the patent records, culminating in article after article complaining “are there any decent human inventors any more?!” Right?

Wrong. Because the question of who can be an inventor, under the patent laws, is a legal one. Just like your dog can’t collect Medicare , your Macbook can’t be named as an inventor in the U.S. patent records. Nor can a business or other entity. Under the U.S. Patent laws, only “persons” can be named as an inventor. (See, U.S. Constitution Article I, Section 8, Clause 8.)

No. AI computer systems can help us innovate, and, dare we say, even “invent” great things, but they will never be recognized as “inventors” legally. So, this is actually a relatively simple question, although it doesn’t sound like one at first. An AI cannot be named as an inventor of a patent.

Ownership of the Inventions by Machines

But the next level questions are where it really gets interesting:

OK, so an AI cannot be recognized as an inventor, but what happens to inventions by machines? Are they owned by the persons, corporations, or entities owning the AI systems? Would that lead to a runaway wealth disparity, as “he with the most machines” owns more and more machines, and all of their inventions, until a few elites own all of the most valuable technology, by a1,000-to-one ration, and then a 1,000,000,000-to-1 ratio, and so on? Are the machines treated as invention assistants, and the humans running them contributing enough to be considered the sole legally recognized co-inventor, taking all of the patent rights? Or are the machine inventions owned by “no one,” and deemed our common heritage, freely available to all, as with other resources? Can we create laws, and, especially, international treaties, to protect humanity’s common interests in scientific progress here?

Even if we do, will the proverbial “evil megacorporations” just hide them in basements, to control the inventions and reap their benefits in secret? Possibly, if they can be hidden, and the owners are clever enough (and we know they will be, because they own this incredibly smart AI). Some inventions are kept as a “Trade Secret” this way. (But that’s a question for another day, for artificial intelligences vastly exceeding our own, or, at least, in a another Beckman Law article).